**

Recent research has unveiled critical insights into the lives and struggles of those affected by the Justinian plague, the first pandemic recorded in history. A team of US-based scientists has confirmed the existence of a mass grave in Jerash, Jordan, which sheds light on the urban dynamics, mobility, and vulnerabilities of individuals during this devastating period in the Byzantine Empire.

Uncovering the Past

The findings, published in the February edition of the Journal of Archaeological Science, reveal that the mass grave represents a singular mortuary event rather than a gradual accumulation of burials typical of traditional cemeteries. This research marks a significant step in understanding the scale and impact of the epidemic that swept through the region from AD 541 to AD 750, claiming millions of lives.

DNA analysis conducted on remains from the Jerash burial site has confirmed the presence of Yersinia pestis, the bacterium responsible for the plague. This research has allowed scholars to reconstruct not just the biological aspects of the pandemic but also the human stories intertwined with it. “Earlier studies identified the plague organism. The Jerash site turns that genetic signal into a human story about who died, and how a city experienced crisis,” explained Rays Jiang, the lead author of the study and an associate professor at the University of South Florida.

The Human Story Behind the Plague

The multidisciplinary team, comprising archaeologists, historians, and geneticists from the University of South Florida, Florida Atlantic University, and the University of Sydney, focused on the lives of the victims. The research indicated a diverse demographic, comprising men, women, and children of varying ages, suggesting that a transient population was caught in Jerash when the plague struck.

“Pandemics aren’t just biological events; they’re social events,” Jiang noted. The research draws parallels between the ancient plague and modern viral outbreaks like COVID-19, highlighting how crises can forcibly gather individuals in urban centres, disrupting their daily lives and movements. “Here, they were brought together by crisis,” she added, emphasising the interplay between disease, urbanisation, and social vulnerability.

Excavating History’s Lessons

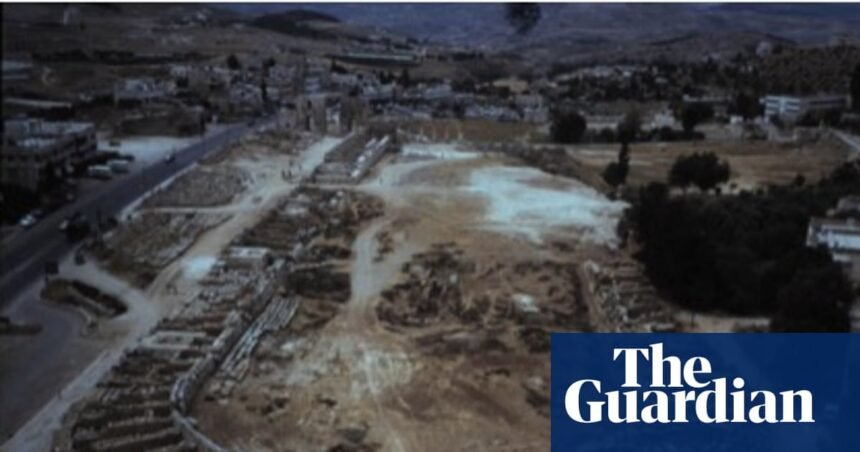

Excavations at the Jerash site revealed that over 200 individuals were interred in the mass grave, located near the city’s famed hippodrome, often referred to as the Pompeii of the Middle East due to its well-preserved Greco-Roman ruins. Jiang pointed out the significance of this diverse demographic composition, indicating that the population included slaves, mercenaries, and other transient individuals typical of a bustling trade hub.

Jiang’s research highlights the challenges faced by historians and researchers in substantiating the impact of the Justinian plague, particularly against contemporary narratives that downplay its severity. “There’s a whole school of thought that says the first pandemic did not happen,” she remarked, addressing the scepticism surrounding the historical accuracy of its effects. The existence of the mass grave serves as tangible evidence of the pandemic’s reality, countering arguments that question its significance.

Why it Matters

This research not only enriches our historical understanding of the Justinian plague but also provides valuable insights into how societies respond to pandemics. As we navigate the ongoing repercussions of COVID-19, the lessons drawn from the past become increasingly relevant. The findings underscore the importance of recognising pandemics as complex social phenomena that profoundly affect human lives, challenging us to learn from history as we confront the uncertainties of the present and future.