In a troubling development for the scientific community, early-career researchers in the UK are sounding alarms over impending funding cuts that threaten to decimate the nation’s pool of talent in physics and astronomy. The UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) has announced that grants for projects in particle physics, astronomy, and nuclear physics will see reductions of nearly 30%, with some project leaders bracing for potential cuts as steep as 60%. This drastic financial upheaval follows the shelving of four major infrastructure projects aimed at advancing scientific knowledge, collectively saving the government over £250 million.

A Generation at Risk

The ramifications of these funding cuts are far-reaching. An open letter addressed to Professor Ian Chapman, the UKRI’s chief executive, has been signed by over 500 researchers who warn that the current environment of uncertainty and instability could result in the loss of an entire generation of scientists. Dr. Simon Williams, a postdoctoral researcher at Durham University, epitomises the plight of many. “Realistically, my options are overseas,” he stated. “The likelihood of me moving to Germany for a position is increasing by the day, as the opportunities in the UK dwindle.”

Dr. Claire Rigouzzo, another early-career researcher at King’s College London, has already accepted a post in Europe after being unable to secure employment within the UK. She describes the job market for emerging scientists as one of the most challenging in recent years and highlights a broader concern: “Morale is extremely low across the board,” she lamented, emphasising that even students are aware that science is losing its status as a priority.

The Financial Landscape

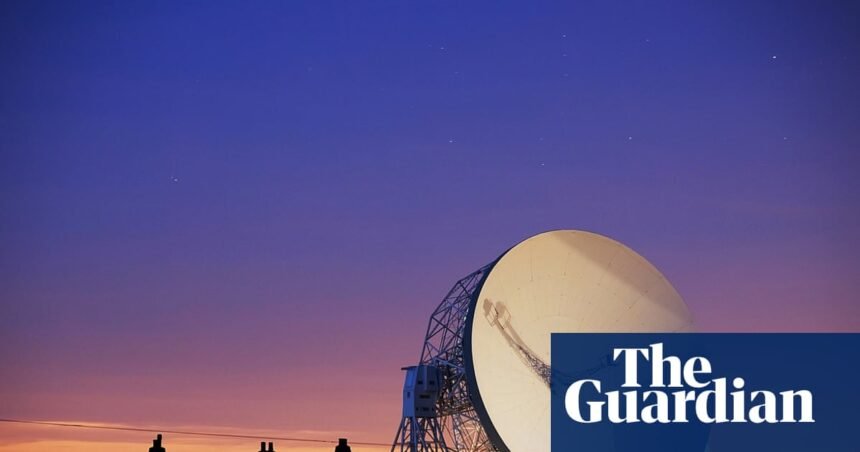

The UKRI currently manages a budget of nearly £9 billion allocated to various research councils, which encompass fields ranging from physical sciences to medical research. However, the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC), which funds key physics research and major facilities like the Diamond Light Source in Oxfordshire, is under pressure to save £162 million by 2030. This financial strain has been exacerbated by rising electricity costs and increased subscriptions to international projects.

Dr. Lucien Heurtier, also from King’s College, has begun seeking opportunities abroad, including positions in China, as he anticipates the end of his contract in September. “No UK university will want to invest in curiosity-driven research if they cannot secure substantial national funding,” he noted, underscoring the gravity of the situation.

The Broader Implications

The potential loss of UK scientists is not just a personal tragedy for those affected; it poses a significant risk to the country’s leadership in global scientific research. The UK has invested heavily in collaborative international projects, such as the groundbreaking Rubin Observatory in Chile, which is set to commence operations this year. However, if funding cuts persist, there may be a dearth of UK astronomers available to contribute. “The timing of these proposed cuts, just as the telescopes begin to deliver results, could not be worse,” warned Professor Catherine Heymans, Scotland’s astronomer royal.

Calls for intervention have emerged from prominent figures within the scientific community. Professor Mike Lockwood, president of the Royal Astronomical Society, urged the government to step in to avert a “catastrophe” for the nation’s scientific landscape. “We cannot afford to lose a whole generation,” he pleaded, emphasising the need for fresh talent to sustain the UK’s standing in international science.

In response to criticisms, Professor Chapman defended the funding cuts, arguing that difficult choices must be made to ensure that remaining resources can be effectively utilised. “When you don’t make choices, everybody misses out because it chokes the system,” he remarked, highlighting the complex balance between funding priorities and competitive capability.

Why it Matters

The cuts to research funding in the UK represent a critical juncture for the scientific community, one that could irreparably damage the nation’s future in science and innovation. As researchers weigh their options against an increasingly unstable backdrop, the UK risks forfeiting its status as a leader in scientific discovery. This crisis not only threatens to undermine decades of scientific progress but also jeopardises the broader societal benefits that come from investing in research and technology. The long-term implications for the UK’s economy, educational institutions, and global scientific reputation are profound, making immediate action imperative.